Tyranny of the Tibetan Majority

By Kaysang

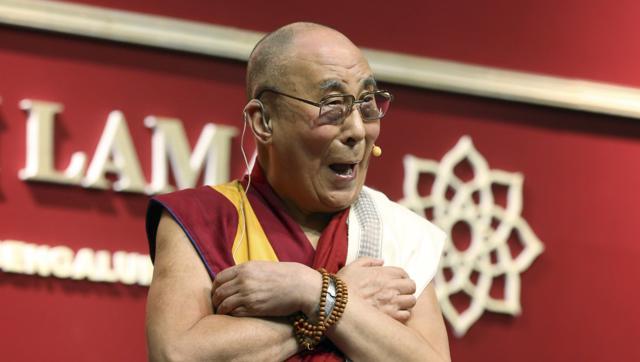

Our exile system of government claims to be a democracy, but recent events have proven it to be quite the opposite. Yes, His Holiness the Dalai Lama has brought about a fundamental change in the system of government, transitioning from a theocracy to a parliamentary theocracy, to one that he hoped, after the devolvement of his political power, would become a truly democratic one. The truth is that we have failed to make his vision of a democratic and pluralistic exile community a living reality.

We have been holding elections for our chithues for decades and this is the third katri/sikyong election to take place. There have been a great many changes and I think public participation in the elections this time around has been much higher than previously seen, probably due to social media and the easy access to information it gives people seeking and disseminating it.

To the untrained eye, it would appear that the Tibetan political environment has started to resemble more the democracy that we aspire to. As a participant in our so-called ‘democracy’ and someone who was brought up in this exile system being taught that we were ‘awarded’ democracy, that our society was really a democratic one, I couldn’t help but have certain expectations and believe certain things about our “mangtsoe chitsok”. My faith in the system was eventually shattered as my exposure developed and I began to acquire the ability to think critically about these issues (one that our education system neither teaches nor encourages).

Due to the ongoing conflicts and controversies within the exile polity, I have been forced to question whether our people truly understand the meaning of democracy. Do we recognize democracy as merely the right to vote for a leader of our choice? Will we embrace a multi-party democracy and accept vocal opposition to the majority? Does it mean just the rule of the majority as we are so used to thinking, as evidenced by the tagline so common in our own personal interactions within a group of friends, where we put things to a vote when making mundane decisions, like which restaurant to go to for dinner: ‘mangtso rey, mangwa doepa ghari yoepa jheya rey’ (it is democracy, we should do what the majority wishes to)? Do we recognize the importance of the protection of minorities of all kinds, be it religious, racial or political? Do we agree that a democracy should guarantee its people a safe space to exercise the right to have extremely conflicting views from each other? Will the Tibetan elite political establishment accept pro-Rangzen leaders and advocates within the halls of government?

When the current Sikyong took office in August 2011, I remember the kind of excitement and hope that he generated, especially among the youth, and despite my personal misgivings about him, I had to admit that the election of a secular Sikyong seemed to be quite a positive step towards democracy. The recent string of disasters engineered by the administration proves to us that we are still deeply mired in exclusionary, non-democratic politics. And yet Sangay has the galls to encourage Tibetans and Tibetan support groups to highlight Tibetan democracy on the world stage, holding it up almost as a near-perfect epitome of a success, even juxtaposing our system against that of Egypt under Mubarak (during the opening address of the Asia Regional Meeting of International Tibet Network this year). To use his own example, “The Egyptians say that they have the freedom to vote but Mubarak has the freedom to count as he wishes.” There is but a tiny difference between our systems then. And when confronted about the absurdity of his statements in the face of the recent elections and the administration’s knack for making extremely inflammatory statements against those who do not comply with everything that CTA deems appropriate (the most recent being Kashag’s 10th December statement against “crazy” talk by people criticizing His Holiness), Sangay told us a couple of children’s stories to fill up 3 minutes with absolute non-answers and then later stopped on his way out to ask me if I was not satisfied with his answer.

If we put it to a poll, probably a hundred percent of the exile population would say that they believe everyone should have the right to the freedom of speech, belief and expression as long as your words, beliefs and actions do not harm others. That is what we grew up learning. What we have actually seen in practice in our society, however, goes against that very belief. Differences in thought and conflict in opinion are only natural in any society and, in a democracy, a characteristic that makes up for the essence of it but we have managed so successfully to foster homogeneity of thought, language, customs, religion and politics in our community that we are now walking dangerously close to the edge of a cliff called intolerance beyond which lies only “tyranny of the majority” (Tocqueville). The uniform narrative of Tibet and the Tibetan identity has been so successfully fed to and adopted by the Tibetan public and the world at large that any diversion from that common narrative is seen as not being Tibetan at all.

An increasingly huge part of this narrative is being played now by conformation with the policy of seeking genuine autonomy under China, a Middle-Way proposed by His Holiness and spun in such a way by politicians that rather than choosing to follow a political ideology that agreed with their own conscience and one that they could decide upon critically by themselves, it became a choice about following our tsawe lama no matter what. This can be evidenced most clearly by the fact that a “unanimous resolution” was adopted by the Members of Parliament on 18th September, 1997:

“An Excerpt from the Official Resolution No. 12/4/97/46 Passed by the Assembly of Tibetan People’s Deputies:

Be it unanimously Resolved that-

1. …suggestions were solicited from all the Tibetan people, within and without Tibet, on the procedure and options of the referendum from 2 September 1995 to 31 July 1997. Based on the overwhelming majority of the suggestions received, the Assembly of Tibetan People’s Deputies implores His Holiness the Dalai Lama to withdraw his call for a referendum, and use his wisdom to decide from time to time the future cause of Tibet and the means to achieve that;”

There was no referendum at all. The people chose to give up their political agency, choosing instead to let their spiritual belief in our leader decide the political future of Tibet.

One cannot help but raise a few questions. Whose “suggestions were solicited”? How far-reaching was the poll within Tibet, since the Tibetan population outside Tibet is believed to be less than 5% of the total? How many people exactly is the “overwhelming majority”? What about those who did not wish to give up Rangzen personally? This happened around 20 years ago. What would the “overwhelming majority” say now? How many youth were consulted at the time? What about the aspirations of all the people like me who were too young at the time to understand politics but have grown up now and are starting to take more responsibility in the movement? What does the “overwhelming majority” inside Tibet feel now, especially after the events following 2008 and the huge changes in political climate that it brought about in their hearts? These are questions that the people in positions of authority in the CTA must answer.

These questions become even more important in the face of blatant suppression of plurality of politics, religion and thought in our community.

Rangzen advocates have been persecuted socially for years. An Indian friend of mine had an amala she didn’t even know yell at her to stop putting her nose in our business because she had seen my friend at events organized by pro-Rangzen groups. I have personally had people on numerous occasions remark derisively, ‘So you’re saying that you’re going to get back our independence’ (‘Tah kherang rangzen lenki yin lapki yoe repa’) just because I had volunteered for Students for a Free Tibet throughout high school and college. These might be just the smallest kinds of examples I can give, but these things have the power to have a profound effect on one when repeated for days on end for years and years. The scariest thing to realize though is that these are the effects of conscious, concentrated efforts by politicians who abuse His Holiness’s name and actually strive to either change public opinion by stressing upon the ‘wishes of His Holiness’ over and over again during official functions and in their speeches, or to change the pro-Rangzen organizations in exile from the inside out. But would His Holiness really wish his name to be used as the biggest weapon in the oppression of those with different political and religious views?

Personally, I do not subscribe to either. I believe that the policy of Umay-lam makes sense when you think of pragmatism in maintaining diplomatic relationships, but that Rangzen organizations are instrumental in keeping the Tibetan movement alive, in rejecting Beijing’s legitimacy and hopefully gaining us leverage one day soon through successful campaigns to actually bring the Chinese to the table for negotiations. This actually helps the official policy of the Tibetan government, who themselves have failed to devise practical plans both on how to gain a little bit of an upper hand on the processes of dialogue and on how to attract the large population of Tibetan youth to this core official policy. Going around settlements and boarding schools just to indoctrinate students is not going to work. The call for Rangzen is deemed to be radical and foolish and treated as going against the principles of nonviolence that the Tibetan movement is known for. The irony lies in the fact that activists working for Rangzen have always been the one who have actively looked for solutions to our problem, they’re the ones who have actually studied nonviolent direct action, read countless books and applied it practically by setting up an institute (Tibet Action Institute), training the youth in nonviolent resistance (through programs like the Lhakar Academy in which I took part where no one tries to brainwash people – they don’t even talk about ideology), enabling people to use this training in organizing campaigns against the Chinese government and empowering Tibetans with knowledge on digital security. Many in higher positions of power in the CTA are merely using nonviolence to not do anything concrete when it comes to pushing the movement forward and keeping it from dying. For them, nonviolence seems to be synonymous to non-action. We are political refugees, a people whose country is being strangled to death by China. It is not just enough that CTA is taking care of those in exile; they also need to look at ways to first enable themselves to negotiate politically and actively involve the youth.

Most importantly, I see the enormous potential for growth that our movement has if we could – impossible though it seems to me right now – remember that the less than 5% population fighting over ideology does not really serve our ultimate goal: to relieve the suffering of the Tibetans inside Tibet who are living a life that we cannot even begin to imagine. I think it would bring amazing results if the CTA could put aside their fear of antagonizing the Chinese and find a way to work with pro-Rangzen organizations on bigger collaborative campaigns. It is entirely possible that my views are indicative of my tendency to look at the positive in everything in life, some might even call it naïveté. After all, I am no expert in politics. But one thing I can be sure of is that our society is being polarized to such an extent by self-serving politicians and self-appointed protectors of the common good of the Tibetan people in the name of ‘respecting the Dalai Lama’s wishes’ and ‘unity’ that I am scared to speak up even for more tolerance in our community lest I be labeled a radical as well, which has actually already happened (I have been called Lukar Jam’s ‘aptuk’ several times, ‘jokingly’). The proponents of Umay-lam seem to be missing the whole point of the concept of the middle way on which it was based and Rangzen advocates are convinced that their way is the only way. Yet both sides seem to be forgetting that this is the kind of ideological debate that is so complicated and multi-layered that one or the other would never triumph over the other in the foreseeable future.

The writer is a graduate in literature from the Delhi University, and currently resides in Dharamshala.