Author Chan Koonchung finds humour in China-Tibet dynamic

South China Morning Post | May 25, 2014

Chan Koonchung satire shows how inequalities of power warp the China-Tibet relationship, writes Kate Whitehead

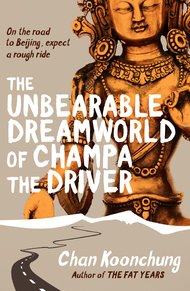

The Unbearable Dreamworld of Champa the Driver

by Chan Koonchung (translated by Nicky Harman)

Penguin Random House

5 stars

Chan Koonchung’s latest work to be translated into English is not your average Tibet novel. Mostly, these follow one of two well-worn paths: either a romantic account of old Tibet, thick with nostalgia, mysticism and prayer flags, or a fiercely political polemic that lashes out at the injustices suffered by Tibetans.

But The Unbearable Dreamworld of Champa the Driver follows a completely different road map. It’s on its own superhighway, blazing a modern trail with a likeable if lost character in the driver’s seat. That’s not to say the novel isn’t romantic – there’s plenty of lovin’ and some rather raunchy boudoir scenes. And political – anyone familiar with the internationally acclaimed author’s work will know he doesn’t shy away from sensitive issues. But the delivery is first-day-of-spring fresh. It’s a fast-paced read, bold and brassy, at times super-sensitive and insightful, with cheeky asides and a raw honesty that will make readers laugh out loud.

Chan is best known for his debut novel The Fat Years, which was dubbed the “Chinese 1984” and banned on the mainland. For 20 years, he’s had a novel exploring the Tibetan and Chinese relationship on his “to-do list”. It was in Hollywood in the early 1990s, researching a film on the prospective succession of the 15th Dalai Lama, that he first became interested in Tibet. The film didn’t happen, but his interest stayed – and The Unbearable Dreamworld benefits from the slow simmering on his creative back burner. The result is a compact novel (less than 200 pages) packed with flavour.

Without question, the Tibet-China relationship is complex, so what better way to explore it than through an equally complicated love affair in which the power is heavily weighted on one side?

Throw in a second sticky situation to further muddle matters and we are close to an analogy of the difficult relationship between one of the world’s superpowers and its restive western region.

Champa, a young Tibetan, is a simple chap. He has a stable job in Lhasa as chauffeur to a successful Chinese art dealer, Plum. Life is uncomplicated. Champa can speak Putonghua and although he’s not permitted a passport, he doesn’t have a gripe against the Chinese. He’s not the sort of guy to get caught up in politics either: he just wants to get on in life.

For Champa, a sure sign that he’s made it would be to move to the Chinese capital and live there like a young Beijinger. But then he starts sleeping with his boss and life gets complicated.

On their first night together, Plum declares him a “sex fiend” – high praise indeed – and he soon adapts to a new life, driving his employer to her appointments when she is in Lhasa and keeping her satisfied after hours.

Plum holds all the power in the relationship: she’s wealthy, successful and older, and she determines when they see each other and what they eat. Champa’s life revolves around her decisions. But he doesn’t complain. It’s a good life, there are undoubted perks, and three years pass quite comfortably.

But then the problems start. To Champa’s horror, he discovers that Plum no longer does it for his “little guy” – he can’t get aroused.

His quest to save his relationship – and his job – by making sure he’s able to perform at night is one of the frankest and funniest sections of the book. He scouts around Lhasa looking for foreign girls to fantasise over, stressing out when he can’t find any and having an amusing conversation in his head when he spots a young girl prostrating herself outside a temple, telling his little guy: “Cut it out. It isn’t proper, leave her alone, she’s saying her prayers.”

It is Plum who inadvertently introduces something that provides a solution to his arousal issue. Satisfied, she again declares: “Champie, you’re a sex fiend.” But it’s a temporary solution and Champa is looking for a way out when Plum’s daughter, Shell, arrives in Lhasa.

It’s not love at first sight. He thinks she looks “like a skinny version of an Angry Bird” and she does her best to ignore her mother’s toy boy, but that doesn’t stop him falling for her – and that’s when things get properly complicated.

Plum and Shell don’t get on, but mother and daughter hold their cards close to their chest and the nature of their feud is one of the mysteries of the book.

In chasing Shell, Champa is following his dream to finally live in Beijing. He takes off in Plum’s SUV – she had suggested that she’d given it to him, but it soon becomes obvious that’s conditional. The crazy three-day drive on the highway is compelling – wild and ruminative in turn, it will surely earn The Unbearable Dreamworld a cult fiction spot.

The road trip is made richer by Nyima, a chatty, philosophical hitchhiker Champa picks up on the way, and it’s marked by a horrific accident they come across, a collision so violent the head of one of the drivers is severed. They stop the car and Nyima whispers in the ear of the decapitated head. He continues talking when they get back in the car, a steady stream of stories about Tibet and China – “the entire Tibet-Qinghai Highway became one long history lesson”, reflects Champa.

In Beijing, Champa gets together with Shell. While his relationship with her is much more of an equal partnership than with Plum, it’s not smooth sailing, chiefly because of the gulf in their cultural experiences. First off, Shell is an animal rights activist and even before anything physical happens between them he’s caught up in her campaign to stop dogs being butchered, which is how he ends up shovelling s*** in the kennels.

It’s not quite the Beijing life he’d imagined but nothing about Shell or the city is as he’d imagined. She is bohemian and quite possibly bisexual, and the city doesn’t welcome him as he’d dreamed.

Getting a job isn’t easy; no one wants to hire a Tibetan. Shell helps him find work as a security guard at a “hotel”, but his hopes that it might be a glamorous position are dashed when he discovers the hotel is in fact a “black jail” where petitioners deemed a nuisance are locked up to keep them out of sight.

One of his responsibilities is serving food to a woman who is kept locked in the basement. Her face disfigured from beatings, the petitioner pleads with Champa for help, for better food. Each day reveals more about the corruption and depravity of the jail, but Champa holds strong to his dream: “I couldn’t be too fussy … If I started with this security work I’d get to know a lot of people and one day someone would recognise my worth and I’d get my chance.”

He dreams of managing a nightclub, disco or karaoke bar while around him the petitioners bang on the bars of their cells and plead to be heard. And as life unravels, an unexpected meeting with Nyima gives him pause for reflection before things go into a serious tailspin. Who will step forward to help rescue him? What does he have left to show for his journey? And where will he go?

Sexual relationships are complicated, some more than others. Shifting balances of power, deliberate manipulations, the force of sexual desire and the ache of longing are par for the course. And relationships are even more complex when there are vast differences in wealth, culture and power between the man and the woman, between Tibet and China.

Chan isn’t out to find solutions to big political questions. Instead he gives us Champa and through the young Tibetan’s dreams, desires and love affairs offers us a contemporary window into the Tibet-China relationship.