Beijing Museum Portrays 1904 Tibet-Britain Conflict as Chinese Resistance

By Tenzin Chokyi

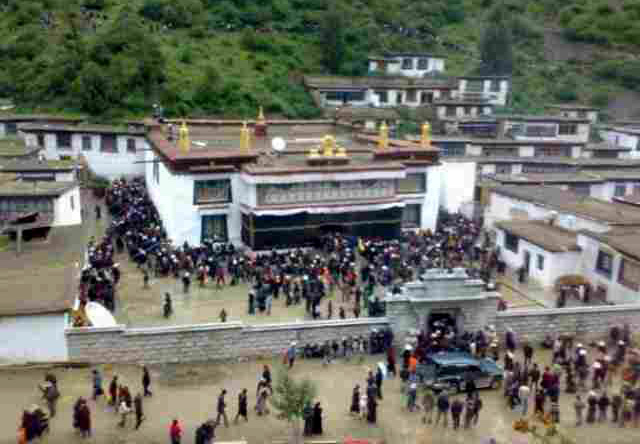

DHARAMSALA 8 Aug: In an absurd move, China has now painted the 1904 Tibetan resistance against the British invasion as part of its own anti‑imperialist narrative. According to a report in China’s state media, Xinhua, on Friday, a recent exhibition at the Museum of Tibetan Culture in Beijing features a digital simulation of the 1904 Tibetan resistance, portraying monks, herders, and peasants bravely defending their homeland against British invaders.

The museum presents this episode as part of a broader story emphasising “collective efforts of all ethnic groups in building a unified country” and “the Chinese central government’s governance over Tibet” in commemoration of the 120th anniversary of the Tibetan resistance against the British invasion.

This narrative is designed to cast China as a modern anti‑imperialist while reinforcing its illegitimate historical claim to Tibet.

In the face of the British invasion of Tibet in 1904, thousands of Tibetan monks, farmers, and militia, mostly armed with swords, matchlocks, and flintlocks, faced British troops equipped with modern rifles and Maxim machine guns. Led by Colonel Francis Younghusband, the British forces had marched from British-controlled India into Tibet, seeking to secure trade routes and counter alleged Russian influence in the then theocratic and isolationist Tibet.

By this time, decades of failed diplomacy, broken treaties, and strategic manoeuvring had paved the way for violence. Tibet’s consistent refusal to engage with foreign powers effectively nullified treaties signed between the British Empire and Qing China, which at the time claimed suzerainty over Tibet but exercised only symbolic control in practice.

Agreements such as the Treaty of Tientsin (1858), the Chefoo Convention (1876), and the 1890 Sikkim–Tibet border treaty were all rejected by the Tibetan government, which maintained that it was not directly subject to Chinese authority.

It was decades of diplomatic frustration and paranoia about growing Russian influence in Tibet that ultimately led to the British invasion of Tibet, prompting Lord Curzon to declare that “the so-called suzerainty of China over Tibet is a constitutional fiction, a political affectation which has only been maintained because of its convenience to both parties.”

The Tibetan resistance against British troops unfolded over roughly eight to nine months, with the first major military clash taking place at Guru in March 1904, where Tibetans, unsupported by any foreign power, including China, which claimed suzerainty then and now insists Tibet has always been part of China, were brutally massacred within minutes by British forces equipped with modern firepower.

Despite this devastating loss, Tibetan forces regrouped and launched a determined defence at Gyantse, where they laid siege to a British fort in one of the most sustained resistance efforts of the campaign.

However, British reinforcements eventually broke the siege, and by 3 August 1904, British troops had marched into Lhasa. The 13th Dalai Lama fled into exile, not to China but to Mongolia, and Tibetan officials, without his authority and in the absence of any Chinese representative, were forced to sign the Lhasa Convention under duress.

With China now asserting that “Tibet has always been part of China since ancient times”, the reality was starkly different. The Qing dynasty’s failure to exercise genuine authority or control over Tibet not only exposed the hollowness of such claims but also fueled the diplomatic frustrations that preceded the British invasion.