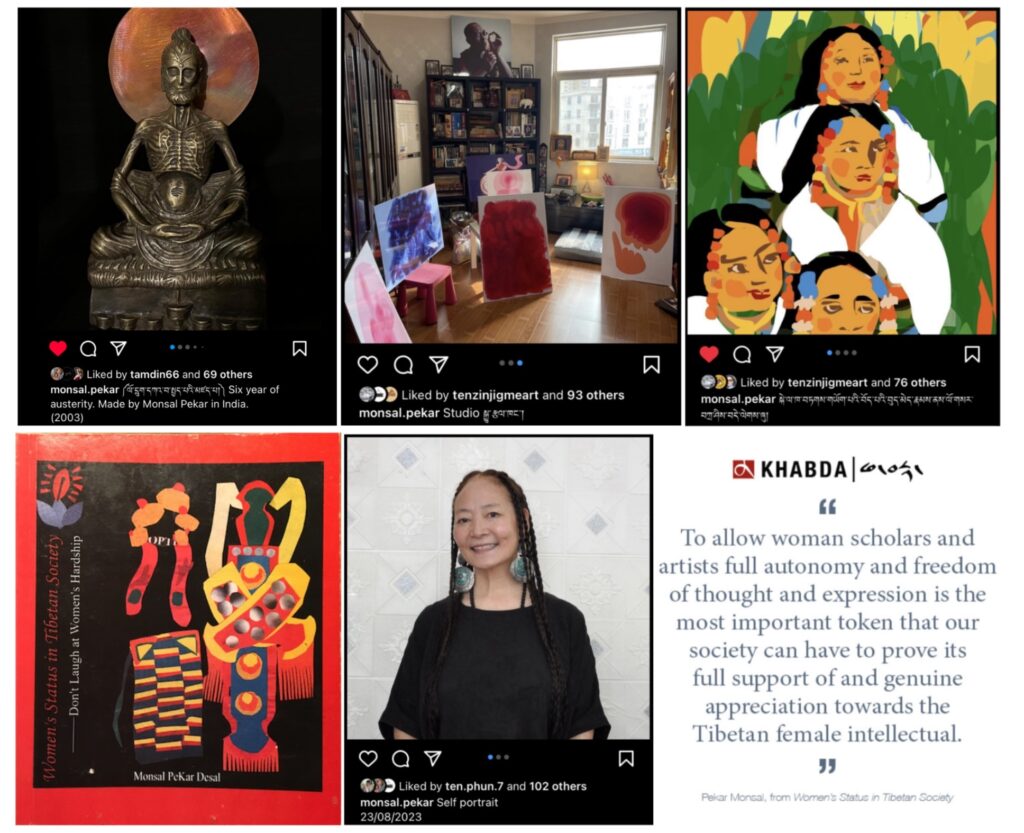

Feature Story: Art in Limbo: Monsal Pekar’s Memorial Doring and Its Fate

By Tsering Choephel

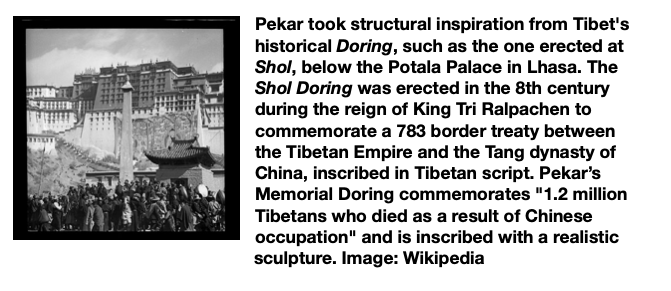

A winter over twenty-three years ago, working solitarily – she was kneading clays and casting them onto the 10-foot base pillar structure to create a Doring (Stone Pillar) as a “Memorial dedicated to the 1.2 million Tibetans who died as a result of Chinese occupation.”

Monsal Pekar was commissioned to create this Memorial Doring by the then administration of the Tibet Museum, which was established by the Tibetan government-in-exile in 1998 at Tsuglagkhang Complex in McLeod Ganj and officially inaugurated by His Holiness the Dalai Lama in April 2000.

One among a few Tibetan women contemporary artists and perhaps the only one living in exile in India at the time, Pekar, after accepting this momentous commission from the Tibet Museum, took it, like any true artist, to her heart and body.

Pekar’s daughter Tenzin Shinyi, who was a year old at the time, told Tibet-Express that her mother, before starting to work on the actual sculpturing of the ‘Doring,’ began by reading books and news on Tibet, to gather facts and to receive inspiration. Going through accounts of Tibetan history, of the tragic period of China’s invasion and its rule that brought immense suffering, deaths, and destruction, Pekar often broke down in tears. A particular scene from an autobiography of a Tibetan man made her – a Tibetan, an artist, a woman, and a mother – heart break into pieces.

In the account, a Tibetan man, passing through a Tibetan village, saw all its residents – men and women, young and old, all slaughtered by the invading Chinese red armies. Among the pooling dead bodies, the man saw an infant child who somehow survived the massacre, clutching his/her mother’s corpse and still suckling at the breast.

On the completed sculptural Doring, among the depicted slaughtered children, men, women, monks, horses, and raging fists and resistance of Tibetans, at the centre right, Pekar sculpted the scene – an infant child still clutching his/her mother’s corpse, suckling at the breast.

Where is this ‘Memorial Doring’ today? What’s the state of it you might ask.

After a new Tibet Museum, a 540-lakh rupees worth of project was built in the T-Building at Gangchen Kyishong and inaugurated in 2022, the old Tibet Museum at Tsuglagkhang Complex was closed, with all its contents packed and moved to the new museum space – except the ‘Doring.’ The ‘Doring’ since then has been going through something like disownment and even faced the threat of dismantling.

Namgyal Monastery, which owns the building where the old museum stood, leased the building in November last year to Rinchen, a Thangka appliqué artist, and a businessman. He is currently revamping the two floors of the building, a shop on the ground floor, and the upper floor as a restaurant. On 24 January, when I went there, Indian labourers had moved the Doring a few feet away from where it used to stand on the upper floor to make space for the renovation work in progress. After the old windows were taken out, Rinchen said he delayed putting up the new windows for two months thinking it would be easier for the museum to move the Doring. When nobody contacted him or showed up at the sight, he came to terms that he must move forward with his work.

Speaking with Rinchen then, he told us of being told by a staff monk from Namgyal Monastery that he could break the Doring down if it was taking up space and hindering his renovation work for the planned restaurant. Fortunately, owing to his own artistic experience as well as affirmation from other voices, most significantly Shinyi’s, that shed light on the significance of Pekar’s “Memorial Doring” historically, artistically, and morally, it still stands today.

Shinyi took it upon herself and reached out in an appeal to the administration of the Tibet Museum, Namgyal Monastery, and Norbulingka Institute one by one, hoping at least one of them would assure her of their willingness to take full responsibility to safeguard and secure the Doring. As you might expect, the Doring means a lot to her personally, she says.

However, no concrete assurance from any of them came her way. When I called the current Tibet Museum director and inquired if the Doring would be moved to the new museum, he said it was next to impossible given the size and weight of the structure and the involved risk of the structure crumbling during movement. During her appeal and inquiry to Namgyal Monastery, she said that a staff monk from the monastery suggested she take the Doring herself if she wanted. Surely she wanted to, given nobody is attending to it. But when a financially capable, experientially plausible, technically, and morally responsible institute like the Tibet Museum ‘thinks’ moving the Doring is not possible, you can’t blame Shinyi for thinking the suggestion was unreasonable.

Someone else approached Shinyi. Learning the current state of the Doring and wanting to secure it, Gong (a pseudonym used on request) contacted Shinyi. Though Shinyi agreed to let him have it, in the end, he too found the task and responsibility too huge. Besides the transportation challenges of this 10-foot several-ton Doring, his unfixed and temporary address would eventually prove the decision unwise, he concluded. But he maintains his opinion, saying, “Tibet Museum has built a state-of-the-art museum, to move this Doring may be challenging but surely a doable task.” The fact that this Doring has been left “unattended and disowned for months is not just disregard for the art itself but for what this art signifies,” he said when we met over tea.

Yesterday, after attending the 65th anniversary of the 12th March Tibetan Women’s Uprising Day commemoration at Tsuklakhang complex, I went inside the building to see whatever has happened to the Doring – an art piece created by one of the most remarkable contemporary Tibetan artists, who paint (in traditional as well as digital), sculpts and writes.

Rinchen employed two labourers who took four days to slice off the back of the Doring to half the weight. Just yesterday he had the Doring drilled and fixed tied on a wall, sacrificing the space he planned for a huge flat TV that I told him is a “priceless bargain.” He said he is going to give it a deserving finishing touch as he completes the renovation, with lightenings and descriptions of the Doring to give it the best presentation he could.

So it appears that Pekar’s Doring which was created within that building is destined to stay in the building. Whoever takes over the building takes over the Doring it seems, like a fate.

The 65th anniversary of both the 10th March and 12th March commemoration just concluded – these historic days remember the bravery and sacrifices of thousands of Tibetan men and women who rose up against the brutal invasion and rule of Communist China in the land of snow. In honouring their heroic acts, we are also reminding ourselves that Tibet is still under occupation and Tibetans are still undergoing colonial treatment under the Chinese Communist Regime.

In times like this, both in individual lives and for the national character, art always holds a special place with its indispensable role – signifying and inspiring, memorialising and creating memory – without which our voices become ten feet less deep, our strength many tons less strong.